Ex-President Barack Obama Orchestrated Tom Perez DNC Chair Victory

Former president Barack Obama, whose legacy is being rapidly dismantled by President Donald Trump and a Republican Party dominating all levels of government, was instrumental in the election of Tom Perez as the new head of the Democratic Party. Perez defeated Congressman Keith Ellison of Minnesota, the initial front-runner in the Democratic National Committee Chair race, by a 235-200 vote on Sunday.

Former president Barack Obama, whose legacy is being rapidly dismantled by President Donald Trump and a Republican Party dominating all levels of government, was instrumental in the election of Tom Perez as the new head of the Democratic Party. Perez defeated Congressman Keith Ellison of Minnesota, the initial front-runner in the Democratic National Committee Chair race, by a 235-200 vote on Sunday.

Obama, whose presidency oversaw a catastrophic collapse in electoral power for Democrats, and who paved the way for Hillary Clinton as the failed Democratic presidential nominee, has publicly expressed his intent to continue to direct the party now that he is out of office.

Ellison entered the race with backing from influential leaders across the Democratic Party, appearing to unify the interest groups of the party that had been split into the camps supporting Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders during the 2016 Democratic primary. Ellison’s career includes environmental-justice and civil-rights organizing, local and national electoral organizing, and effective public engagement on the national stage—perhaps most notably his warning to the nation to take Donald Trump’s presidential campaign seriously in the summer of 2015, while political pundits were treating Trump as a good-for-ratings joke.

Ellison’s campaign faced concerted public attacks against Ellison’s candidacy from anti-Muslim activists and party funders who accused Ellison of being an anti-Semite despite a long record of alliance with and advocacy for progressive Jewish politics.

In addition, Ellison ran a campaign publicly discouraging engagement by the grassroots members of the party, contradicting his own declared vision of a grassroots-driven party.

Meanwhile, Perez rose in favor among the DNC membership after gaining the public endorsement of key Obama allies, foremost among them former Vice President Joe Biden. That Obama was personally backing Perez was widely understood but never directly confirmed.

In the wake of Perez’s victory, Politico’s Edward-Isaac Dovere has reported that Obama himself selected Perez to run and then personally lobbied DNC members on behalf of Perez:[T]he distaste for [Ellison’] approach and profile . . . helped push former President Barack Obama to urge Perez into the race — and continue the support all the way through. He called DNC members himself, and had aides including confidante Valerie Jarrett, former political director David Simas and his White House director of political engagement Paulette Aniskoff working members by phone through the votes on Saturday afternoon. Former Vice President Joe Biden, who officially endorsed Perez, also worked the phones with members.Obama and Biden made a four-point pitch, according to a person familiar with the call strategy: Perez’s unimpeachable progressive credentials at the Justice and Labor departments, his ability to bring people together, his management skills and how he was one of the stars of the Obama administration.

(Some progressive critics have impeached Perez’s record at Justice and Labor, particularly his strong support for the TPP.)

Obama’s direct involvement in the race was not reported until after Perez was elected. Soon after Perez won, Obama made his first public statement on the race, congratulating Perez and his own “legacy”:Congratulations to my friend Tom Perez on his election to lead the Democratic Party, and on his choice of Keith Ellison to help him lead it. I’m proud of all the candidates who ran, and who make this great party what it is. What unites our party is a belief in opportunity – the idea that however you started out, whatever you look like, or whomever you love, America is the place where you can make it if you try. Over the past eight years, our party continued its track record of delivering on that promise: growing the economy, creating new jobs, keeping our people safe with a tough, smart foreign policy, and expanding the rights of our founding to every American – including the right to quality, affordable health insurance. That’s a legacy the Democratic Party will always carry forward. I know that Tom Perez will unite us under that banner of opportunity, and lay the groundwork for a new generation of Democratic leadership for this big, bold, inclusive, dynamic America we love so much.

Obama’s depiction of the Democratic Party as the party of “opportunity” hearkens back to President Ronald Reagan, who frequently described the Republican Party as the party of “opportunity.” After his victory, Perez told Meet the Press “we are the party of opportunity and inclusion.”

In post-election exit interviews, Obama made clear that he intends to maintain control over the Democratic Party, whose problems he perceives to be rooted in messaging failures, not policy weaknesses. He told Rolling Stone that it would be “incorrect” to conclude that the Obama administration neglected rural or working-class communities; instead the discontent is a result of a “communications” problem to be solved by a new “common story” and then “figuring out how do we attract more eyeballs and make it more interesting and more entertaining and more persuasive.”

If you look at the data from the election, if it were just young people who were voting, Hillary would have gotten 500 electoral votes. So we have helped, I think, shape a generation to think about being inclusive, being fair, caring about the environment. And they will have growing influence year by year, which means that America over time will continue to get better. This is a cultural issue. And a communications issue. It is true that a lot of manufacturing has left or transformed itself because of automation. But during the course of my presidency, we added manufacturing jobs at historic rates… The challenge we had is not that we’ve neglected these communities from a policy perspective. That is, I think, an incorrect interpretation. You start reading folks saying, “Oh, you know, working-class families have been neglected,” or “Working-class white families have not been paid attention to by Democrats.” Actually, they have. What is true, though, is that whatever policy prescriptions that we’ve been proposing don’t reach, are not heard, by the folks in these communities. And what they do hear is Obama or Hillary are trying to take away their guns or they disrespect you. I’ll spend time in my first year out of office writing a book, and I’m gonna be organizing my presidential center, which is gonna be focused on precisely this issue of how do we train and empower the next generation of leadership. How do we rethink our storytelling, the messaging and the use of technology and digital media, so that we can make a persuasive case across the country? And not just in San Francisco or Manhattan but everywhere, about why climate change matters or why issues of economic inequality have to be addressed.

Well, the most important thing that I’m focused on is how we create a common set of facts. That sounds kind of abstract. Another way of saying it is, how do we create a common story about where we are. It’s gonna require those of us who are interested in progressive causes figuring out how do we attract more eyeballs and make it more interesting and more entertaining and more persuasive.

Obama told NPR and David Axelrod that his post-presidency plan is to focus on “developing young Democratic leaders” to continue the same policies as his administration but with a better messaging approach to ex-urban and rural voters.

Now, with his pick as the head of the Democratic Party, a newly re-launched Organizing for Action, and a foundation overseen by Silicon Valley and Wall Street executives, the former president is in a strong position to put his plan to defend his presidency’s reputation through a new generation of Democratic politics into action.

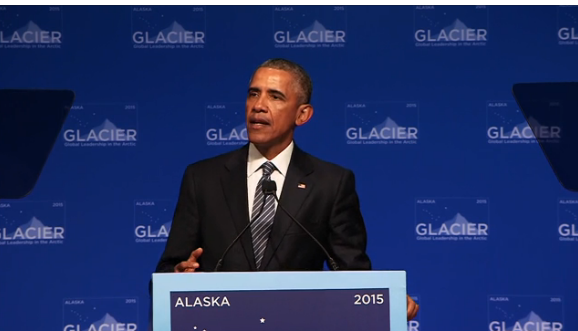

President Obama: Politicians Need to Lose Their Seats for Climate Inaction

In a far-ranging discussion with actor-activist Leo DiCaprio and climate scientist Katherine Hayhoe, President Barack Obama defended his approach to climate change and expressed concern about the future.

“We’ve got to change our politics. And as Leo said, it’s got to come from the bottom up. Until on a bipartisan basis, politicians feel that their failure to address this will cost them their seats, potentially, or will threaten their careers, then they’re going to continue to operate in ways that I think are really unproductive.”

In the same discussion, Obama repeated his questionable claim that the domestic fracking boom has led to a decrease in greenhouse pollution, asserting “the fact that we’re transitioning from coal to natural gas means less greenhouse gases.”

He also repeatedly characterized climate change as primarily a problem for future generations, saying that “climate change is almost perversely designed to be really hard to solve politically because it is a problem that creeps up on you.” He even repeated the now-debunked canard that there is “no single hurricane or tornado or drought or forest fire that you can directly attribute to climate change.”

Just last month, Obama visited the victims of the catastrophic Baton Rouge floods. Consoling the survivors of climate disasters has been a ritual of his presidency. With a fierce Hurricane Matthew churning towards a Florida landfall, the president will likely have another major opportunity to witness the creeping problem of global warming first hand at least once more.

Transcript:

THE PRESIDENT: Hello, everybody. (Applause.)

MR. DICAPRIO: I want to thank you all for coming here this evening. I want to particularly thank our President for his extraordinary environmental leadership. (Applause.)

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you.

MR. DICAPRIO: Most recently, in protecting our oceans.

Katharine, thank you for the great work you do on climate change and in helping improve preparedness of communities to deal with the impacts of climate change. (Applause.)

And thank all of you for showing up here this evening.

Tonight I am pleased to present the U.S. premier of my new documentary, “Before the Flood.” This was a three-year endeavor on the part of myself and my director, Fisher Stevens. Together we traveled from China to India, to Greenland to the Arctic, Indonesia to Micronesia, to Miami to learn more about the effects of climate change on our planet and highlight the message from the scientific community and leaders worldwide on the urgency of the issue.

This film was developed to show the devastating impacts that climate change is having on our planet, and more importantly, what can be done. Our intention for the film was to be released before this upcoming election. It was after experiencing firsthand the devastating impacts of climate change worldwide, we, like many of you here today, realize that urgent action must be taken.

This moment is more important than ever where some power leaders who not only believe in climate change but are willing to do something about it. The scientific consensus is in, and the argument is now over. If you do not believe in climate change, you do not believe in facts or in science — (applause) — or empirical truths, and therefore, in my humble opinion, should not be allowed to hold public office. (Applause.)

So, with that, I’m so very honored and pleased to be joined onstage with one of those leaders — a President who has done more to create solutions for the climate change crisis than any other in history — President Barack Obama. (Applause.)

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you.

Q Along with leading climate scientist, Katharine Hayhoe, for this conversation about how we can make real progress on this issue.

So, with that, let us begin with the first question. President Obama, you’re nearing the end of your second term as President. You’ve had an opportunity to reflect on the issues facing our country and our planet. How do you grade the global response to the climate change movement thus far?

THE PRESIDENT: We get an incomplete. But the good news is we can still pass the course if we make some good decisions now. So, first of all, I just want to thank everybody who’s been here — all day, some of you. (Applause.) Everybody who’s been involved in South by South Lawn. It looked really fun. (Laughter.) I was not allowed to have fun today. I had to work — although I did take some time — you guys may have noticed — to take a picture with one of the Lego men. (Laughter.)

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Happy anniversary, Mr. President!

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you. It is my anniversary today. (Applause.) We celebrated it yesterday — 24 years FLOTUS has put up with me. (Laughter.)

I want to thank Leo for the terrific job he’s done in producing the film, along with Fisher. All of you will have a chance to see it at its premier tonight. And I think after watching it, it will give you a much better sense of the stakes involved and why it’s so important for all of us to be engaged.

And I want to thank Katharine from Texas Tech.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Wooo —

THE PRESIDENT: There you go, we got a couple Texas Tech folks in here. But because Katharine, in addition of being an outstanding climate scientist, is a person of deep faith and she has really done some amazing stuff to reach out to some unconventional audiences to start fostering a broader coalition around this issue.

To your question, Leo, we are very proud of the work that we’ve been able to do over the last eight years here in the United States — doubling fuel efficiency standards on cars; really ramping up our investment in clean energy so that we doubled the production of clean energy since I came into office. We have increased wind power threefold. We’ve increased the production of solar power thirtyfold. We have, as a consequence, slowed our emissions and reduced the pace at which we are emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere faster than any other advanced nation.

And that’s the good news. The other big piece of good news was the Paris agreement, which we were finally able to get done. (Applause.) And for those of you who are not as familiar with it, essentially what the Paris agreement did was, for the first time, mobilize 200 nations around the world to sign up, agree to specific steps they are going to take in order to begin to bend the curve and start reducing carbon emissions.

Now, not every country is doing the exact same thing because not every country produces the same amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, per capita. So the expectation is, is that a country like the United States is going to do more than a small, underdeveloped country that doesn’t have the same scale of emissions.

But the good news about the Paris agreement was it committed everybody to do something. And although if you add it up, all the commitments that were made by all 200 nations, it would still not be sufficient to deal with the pace of warming that we’re seeing in the atmosphere. What it does do is set up for the first time the architecture, the mechanism whereby we can consistently start turning up the dials and reducing the amount of carbon pollution that we’re putting into the atmosphere.

And one last piece of good news about that is that I anticipate that this agreement will actually go into force in the next few weeks. India, just this past week, signed on. And we’re going to get a few more nations signing on. (Applause.) And so, officially, this agreement will be into force much faster than I think many of us anticipated when we first organized it.

Last two points, little tidbits of good news. This week we’ll begin negotiations on an aviation agreement, an international aviation agreement, where all airlines and major carriers around the world begin to figure out how they can reduce the amount of greenhouse gases that they’re emitting, which can make a big difference. And over the next couple weeks, we’re also going to be negotiating around something called hydrofluorocarbons — or HFCs — which are other sources of greenhouse gases that, if we are able to reduce them, can have a big impact, as well.

So even with the Paris agreement done, we’re still pushing forward hard in every area that we can to keep making progress. But, having said all that — and this is where you’ll need to hear from Katharine because in the nicest way possible she’s going to scare the heck out of you as a precursor to the film.

What we’re seeing is that climate change is happening even faster than the predictions would have told us five years ago or 10 years ago. What we’re seeing is changes in climate patterns that are on the more pessimistic end of what was possible — the ranges that had been discerned or anticipated by our scientists — which means we’re really in a race against time.

And part of what I’m hoping everybody here comes away from is hope that we can actually do something about it, but also a sense of urgency that this is not going to be something that we can just kind of mosey along about and put up with climate denial or obstructionist politics for very long if, in fact, we want to leave for the next generation beautiful days like today. (Applause.)

MR. DICAPRIO: With that, Katharine, all the environmental crises we face have a huge toll on humanity — on poverty, security, public health, and disaster preparedness. The interconnected nature of our planet means that no country or community is going to be immune to any of these threats. What are the most urgent threats to our modern day civilization? And where do you feel the solutions lie?

MS. HAYHOE: Well, how many hours do we have again? (Laughter.) It’s true, when we think of global issues, we think of poverty; we think of hunger; we think of disease; we think of people dying today from preventable causes that no one should be dying from in 2016.

And when we’re confronted with these situations head on — and I, myself, spent a number of years as a child growing up in South America, so I know what this looks like — we think to ourselves, climate change, it’s important, but we can deal with it later. We can no longer afford to deal with it later. Because if we want to fix poverty, if we want to fix hunger, if we want to fix inequality, if we want to fix disease and water scarcity, we are pouring all of our money, all of our effort, all of our hope and prayers into a bucket, and the bucket has a hole in the bottom. And that hole is climate change. And it is getting bigger and bigger.

To fix the global issues that we all care about, including environmental issues, including humanitarian issues, we can no longer leave climate change out of the picture because we will not be able to fix them without it.

MR. DICAPRIO: Mr. President, in “Before the Flood,” we see examples of the environmental impacts of corporate greed — corporate greed from the oil and gas industry. For example, it’s happening right now in Standing Rock. But some companies are starting to realize that addressing the climate change issue can actually spur economic activity. How do you get more companies to start moving in this direction, to take fundamental action into their business decision?

THE PRESIDENT: Well, companies respond to incentives. And the question then becomes, can we harness the power and the creativity in the marketplace to come up with innovation and solutions?

And, look, the economics of energy are extremely complicated. But let me just simplify it as much as possible. Dirty fuel is cheap — because we’ve been doing it a long time, so we know how to burn coal to produce electricity. We know how to burn oil, and we know how to burn gas. And if it weren’t for pollution, the natural inclination of everybody would be to say let’s go with the cheap stuff.

And particularly when it comes to poor countries — you take an example like India, where hundreds of millions of people still don’t have electricity on a regular basis, and they would like to have the standards of living that, if not immediately as high as ours, at least would mean that they’re not engaging in backbreaking work just to feed themselves, or keep warm — it’s completely understandable that their priority is to create electricity for their people.

And if we’re going to be able to solve this problem, we are going to have to come up with new sources of energy that are clean and cheap. Now, that’s going to involve research; it’s going to involve investment in R&D. And there are going to be startups and innovators — and there are some in this audience who are doing all kinds of amazing things. But it takes time to ramp up these new energy sources. And we’re in a battle against time.

The best way we can spur that kind of innovation is to either create regulations that say, figure it out, and if you don’t figure it out then you’re going to pay a penalty, or to create something like a carbon tax, which is an economic incentive for businesses — (applause) — to do this.

Now, I’ll be honest with you. In the current environment in Congress, and certainly internationally, the likelihood of an immediate carbon tax is a ways away. But if you look at what we’re doing just with power plants, a major source of greenhouse gases, we put forward something called the Clean Power Plan —clean power rule — as a centerpiece of our climate change strategy. And we did this under existing authorities under the Environmental Protection Act.

And what we’re saying to states is, you can figure out the energy mix, but you’ve got to figure out how to reduce your carbon emissions, and you need to work with your utilities and you need to work with your companies, and come up with innovative solutions. And we’re not going to dictate to you exactly how do you do it, but if you don’t start reducing them you’re going to have problems. And we’ll come up with a plan for you.

So the good news is that in the past, where we create an incentive for companies, it turns out that we’re more creative, we’re more innovative, we typically solve the problem cheaper, faster than we expected, and we create jobs in the process.

And if you doubt that, I’ll just give you two quick examples — because this is probably a pretty young audience, and I know this is going to seem like ancient history, but when I arrived in college in Los Angeles in 1979, I still remember the sunsets were spectacular. I mean, they were just these amazing colors. It was like I’d never seen them before — because I was coming from Hawaii. And I started asking people, why are the sunsets here so spectacular? They said, well, that’s all smog, man. It’s creating this psychedelic stuff that normally is not seen in nature — (laughter) — because the light is getting filtered in all kinds of weird ways.

You couldn’t run for more than 10, 15 minutes on an alert day without really choking up — the same way you still do in Beijing. Well, L.A. is not pristine today, but we have substantially reduced smog in Los Angeles because of things like the catalytic converter and really rigorous standards. (Applause.)

The same is true with something called acid rain. In the Northeast, there was a time where — Doc, make sure I’m getting this right — it’s Sulphur dioxide, right?

MS. HAYHOE: Yes.

THE PRESIDENT: Which was being generated from industrial plants, was going up into the atmosphere and then coming down in rain. It was killing forests all throughout the Northeast. And through the Clean Air Act, they essentially set up the equivalent of a cap and trade system. They said, companies, you figure out how to reduce your carbon dioxide emissions; we won’t tell you exactly how to do it, but we’re going to give you a powerful incentive — we’ll penalize you if you don’t do it. You can capture some of the gains if you do do it.

Most of you don’t hear anything about acid rain anymore, even though it was huge news 25, 30 years ago, because we fixed it.

And the last example I’ll use is the ozone. It used to be that one of the things we were really scared about was the ozone layer was vanishing. And when I was growing up I wasn’t sure exactly what the ozone layer was, but I didn’t like the idea that there was a big hole that was developing in the atmosphere. (Laughter.) It just didn’t sound good. And it turned out that one of the main contributors to this was everybody was using deodorant with aerosol. And so everybody starting getting speed strips, or whatever. (Laughter.)

And it wasn’t that big of an inconvenience. Deodorant companies still made money. But something that I was amazed by — and it gives you a sense of nature’s resilience when we do the right thing — we just have gotten reports over the last couple of months that that hole in the ozone layer is beginning to close, which is amazing. (Applause.)

And all it took was people not using aerosol deodorant.

MS. HAYHOE: A few more things. (Laughter.)

THE PRESIDENT: There were a couple other things. I’m exaggerating. (Laughter.) Well, but essentially, we regulated the kinds of pollutants that were creating this hole without impeding our economic development. Nobody misses what we — because companies were innovated enough to come up with substitutes that worked just fine.

And that’s the basic strategy that we’ve got to employ here. We’ve got to give incentives to companies — startups, existing companies. And we’re going to have to do that initially, country by country. But America has got to lead the way because not only do we have the highest carbon footprint, per capita, but also because we happen to be the most innovative, dynamic business and entrepreneurial sector in the world. And if we create incentives for ourselves, we will help to fix this problem internationally. I’m absolutely confident of the matter.

MR. DICAPRIO: Back to something you mentioned earlier, Mr. President, which I’d like both of you to talk a little bit about — the United States, as you said, has been the largest contributor to global emission in history. And as you said, as well, we need to set the example for the rest of the world to follow. Throughout my journey, most of the scientific community truly believes that the silver bullet to combat this issue is a carbon tax.

Now, a carbon tax, as complex as it is to implement, I would imagine, is something that needs to come from the people. It needs to come from the will of the people, which means there needs to be more awareness about this issue. Do you think that I will get to see a carbon tax in the next decade? Will we get to see this in our lifetime? Because most scientists specifically point to the idea that that’s going to be the game-changer.

MS. HAYHOE: I think he knows the likelihood of that more than I do, but I do know that one of my absolute favorite organizations is Citizens Climate Lobby, and they are founded on the premise of a simple carbon tax — nothing fancy; no difficult regulations; no three feet of code. It’s putting a price on carbon to allow the market to then figure out what’s the cheapest way to get our energy.

MR. DICAPRIO: Can you explain to our audience what a carbon tax would mean?

MS. HAYHOE: Sure. In very basic terms, when you burn carbon it has harmful impacts on us, on our health, on our water, on our economy, on our agriculture, even on our national security. By putting a fee on that carbon, it makes certain types of energy more expensive and it makes other types of energy less expensive.

And the way I like it — there’s many different flavors — the kind I like is where that extra revenue is returned to us through our taxes and also used to incentivize technological development.

MR. DICAPRIO: Or it could be given to education, for example.

MS. HAYHOE: Yes.

MR. DICAPRIO: Bravo. (Laughter and applause.)

Katharine, you live in Texas.

MS. HAYHOE: I do. (Applause.) So do people over there.

MR. DICAPRIO: They’ve experienced unprecedented drought and floods in the past five years, and they’re also a major energy producer. AS you travel the state, what are the biggest misperceptions you hear from climate skeptics who often say these changes are the result of the cyclical nature of our planet’s temperature patterns? And how do you change their minds?

MS. HAYHOE: Any of us who pays attention to the weather, we know that we have cold and hot; we have dry and we have wet. And everybody who’s ever been to Texas knows that it looks more like this. Yes. So you might say, well, then, why does it matter if our weather is incredibly variable anyway? It matters because in a warmer planet, it’s taking that natural pattern of variability that brings drought and flood, heat and cold and it was stretching it.

So our heavy rainfalls are getting more extreme, because in a warmer atmosphere, the oceans are warmer and so more water evaporates. So the water is just sitting out there waiting for a storm to come through, pick it up and dump it on us — just as happened here in recent days, as it happened in Baton Rouge a little while ago.

And if you read the reports of the meteorologists and the weather people talking about these heavy downpours you’re experiencing, you’ll see this phrase they repeat again and again — the warm oceans — and again, this year is a 99 percent chance of being again the warmest year on record after last year and the year before — the warm oceans are providing a nearly infinite source of moisture for these storms. But at the same time, when we’re in a dry period, as we get all the time in Texas, and it’s hotter than average, then all of the moisture in our soil and our reservoirs evaporates quickly, leaving us dryer for longer periods of time.

So, yes, we know natural cycles are real. But we know that climate change is stretching that natural pattern, impacting us and our economy.

Here’s the cool thing about Texas, though. What do you think when you think of Texas?

THE PRESIDENT: Wind power.

MS. HAYHOE: Wind power — yes.

THE PRESIDENT: I cheated.

MS. HAYHOE: He cheated. He knows the answer. (Laughter.) Texas knows energy. And here’s the cool thing about Texas. Did you know that already Texas is getting 10 percent of its electricity from wind? On a windy night, we get 50 percent of our energy from wind.

Every time I go south from where I live there are a new crop of wind turbines going up. And a couple years ago, I spent an afternoon on a farm down in Manisha, Texas, with a very conservative farmer, wasn’t too sure about this scientist showing up, but I was from Texas Tech. And after about an hour we figured out that I knew somebody who went to his church, and vice versa. So we were good. And I got the nerve to ask him, well, I notice that your neighbor has wind turbines all the way up to the edge of your land, and you don’t have any wind turbines. You have a couple of oil wells. Is there any reason you don’t have wind turbines?

And I expected something along the lines of, oh, those are for those sissy tree-huggers, or something. And he said, yes, there is a reason. And I said, well, may I ask what it is? And he said, I’ve been on the list for two years. I’ve been waiting for my wind turbine. I said, well, why do you want one. He said, because the check arrives in the mail.

In Texas, we have entire towns going 100 percent renewable because it is the cheapest way for them to get their energy. We have Fort Hood, which is the biggest military installation in the U.S., signing a new electricity contract for wind and solar because they can save the American taxpayer $165 million by going green. (Applause.)

Green is no longer just a color of money — or the color of trees, I should say. Green is also increasingly in Texas, around the U.S., and even in China, becoming the color of money, as well. Wind and solar are the way of the future. And we’re seeing it happen — as a scientist, though, I have to say my only concern is we’re not seeing it happen fast enough.

MR. DICAPRIO: Mr. President, this has been an unusual election year, to say the least. (Laughter.) And Gallup regularly polls Americans with an open-ended question about the issues that matter most to them. And the environment consistently polls low on that list, around 2 percent. As you know, climate change is a long-term problem. It requires long-term solutions. How can we all do a better job of engaging the public, especially those who are skeptical, in a meaningful and productive debate about the urgency of these issues and inspire them to be a part of the solution now?

THE PRESIDENT: Well, climate change is almost perversely designed to be really hard to solve politically because it is a problem that creeps up on you. There’s no single hurricane or tornado or drought or forest fire that you can directly attribute to climate change. What you know is, is that as the planet gets warmer the likelihood of what used to be, say, a hundred-year flood, that’s supposed to happen only every hundred years, suddenly starts happening every five years, or every two years.

And so the odds just increase of extreme weather patterns. But people, they don’t see it as directly correlated. And the political system in every country is not well-designed to do something tough now to solve a problem that people are really going to feel the impacts of in the future. The natural inclination of political systems is to push that stuff off as long as possible.

So if we are going to solve this problem, then we’re going to need some remarkable innovation. Katharine is exactly right that solar and wind is becoming a job generator and an economic development engine. But what’s also true is we’re going to need some real innovation in things like, for example, battery storage. How do we keep wind and solar stored without too much leakage so that when the wind is not blowing or the sun is not shining, we still have regular energy power. We’re still going to need some really big technological breakthroughs.

But with the technology that we have right now, my goal has been to build that bridge to this clean energy future. To make sure that over the next 20 years, using existing technologies, we do everything we can even as we’re creating the even more innovative technology, so that by the time those technologies are ready we haven’t already created an irreversible problem.

And that’s going to require mobilization. It is going to require us all doing a better job of educating ourselves, our friends, our neighbors, our coworkers, and ultimately expressing that in the polls. And in order to do that, I think it is important for those of us who care deeply about this — and Katharine is a wonderful example of the right way to do it — to not be dismissive of people’s concerns when it comes to what will this mean for me and my family. Right?

So if you’re a working-class family, and dad has to drive 50 miles to get to his job, and he can’t afford to buy a Tesla or a Prius, and the most important thing to him economically to make sure he can pay the bills at the end of the month is the price of gas, and when gas prices are low that means an extra 100 bucks in his pocket, or 200 bucks in his pocket, and that may make the difference about whether or not he can buy enough food for his kids — if you just start lecturing him about climate change and what’s going to happen to the planet 50 years from now, it’s just not going to register.

So part of what we have to do I think is to engage, talk about the science, talk about the concrete effects of climate change. We have to make it visual and we have to make it vivid in ways that people can understand. But then we also have to recognize that this transition is not going to happen overnight, and you’re not starting from scratch. People are locked into existing ways of doing business.

Look, part of the reason we have such a big carbon footprint is our entire society is built around interstate highway systems and cars. And you can’t, overnight, suddenly just start having everybody taking high-speed trains because we don’t have any high-speed trains to take. And we have to build them. And we should start building them. But in the meantime, people have to get to work.

So I think having an understanding that we’re not going to complete this transition overnight, that there are going to be some compromises along the way, that that’s frustrating because the science tells us we don’t have time to compromise; on the other hand, if we actually want to get something done, then we got to take people’s immediate, current views into account. That’s how we’re going to move the ball forward.

And I’ll just give you one example. And generally — this is a pretty sympathetic crowd, but some folks will push back on this. When you think about coal, we significantly reduced the amount of power that we’re generating from coal. And it’s going to continue to go down. Well, number one, coalminers feel like they’ve been battered, and they often blame me and my tree-hugger friends for having created real economic problems in places like West Virginia, or parts of Kentucky, or parts of my home state of southern Illinois.

Interestingly enough, one of the reasons why we’ve seen a significant reduction of coal usage in the United States is not because of our regulations. It’s been because natural gas got really cheap as a consequence of fracking. Now, there are a lot of environmentalists who absolutely object to fracking because their attitude is sometimes it’s done really sloppy and releases methane that is even a worse greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. It leaks into people’s water supplies and aquifers, and when done improperly can really harm a lot of people. And their attitude is we got to leave that stuff in the ground if we’re going to solve climate change.

And I get all that. On the other hand, the fact that we’re transitioning from coal to natural gas means less greenhouse gases. Same thing with nuclear power. People don’t like nuclear power because they have visions of Chernobyl or Three Mile Island, what are we doing with the storage of the waste. Nuclear power generally evokes a lot of stuff in our imaginations. But nuclear power doesn’t emit greenhouse gases.

So we’ve got to make some decisions. If we’re going to get India or China to actually sign on to reducing carbon emissions, then we’re going to have to have a conversation with them about nuclear power, and help them with technologies that ensure safety and we can figure out how to store it until we invite the perfect energy source — crystals or whatever, and Scotty is there beaming us up — (laughter.) But until then, we’ve got to live in the real world.

So I say all that not because I don’t recognize the urgency of the problem. It is because we’re going to have to straddle between the world as it is and the world as we want it to be, and build that bridge. And what I always tell my staff, and what I told our negotiators during the Paris agreement is better is good. Better is not always enough; better is not always ideal, and in the case of climate change, better is not going to save the planet. But if we get enough better, each year we’re doing something that’s making more progress, moving us forward, increasing clean energy, then that’s ultimately how we end up solving this problem.

And that’s when we can start creating political coalitions that will listen to us, because we’re actually recognizing that some people have some real concerns about what this transition is going to do to them, to their pocketbook, and we’ve got to make sure that they feel like they’re being heard in this whole process. (Applause.)

MS. HAYHOE: Absolutely. I couldn’t agree more, first of all. And second of all, I think that this really underscores one of the biggest lessons that I, as a scientist, have learned. So, so often we feel like facts and information are what’s going to make people care.

And so many times, I have somebody come into me and say, Katharine, if you could just talk to my mother, if you could just talk to my brother-in-law, if you could just talk to our city councilperson and give them the facts — it’s real, it’s us, it’s bad, we have to fix it — that will change their minds. The biggest thing I’ve learned is that facts are not enough. In fact, the more literate we are about science, the more polarized we are about climate change.

The most important thing to do is not to pile up scientific reports until they reach a tottering pile of about eight feet, where they’ll tip over and crush somebody. The most important thing to do is to connect this issue to what’s already in our hearts. Because one of the most insidious myths I feel like we’ve bought into is that I have to be a certain type of person to care about climate change. And if I am not that person, then I don’t care about it because I care about these other things. But the reality is, is that if we’re a human living on this planet — which most of us are — as long as we haven’t signed up for the trip to Mars — I don’t want to know if anybody has. I think you’re crazy. (Laughter.)

MR. DICAPRIO: I did —

MS. HAYHOE: Oh, you did? Oh, I’m sorry, I take that back. (Laughter.)

THE PRESIDENT: I think you’ll acknowledge he’s crazy. (Laughter.)

MS. HAYHOE: All right, we’ll go with that. (Laughter.) So if we’re a human living on this planet, this is the only planet we have. It’s our home. If we’re a parent, we would do anything for our children’s sake. If we’re a businessperson, we care about the economy. We care about the community that we live in. We care about our house. We care about the fact that we want to have clean air to breathe; we want to have enough water to drink; we want to have a safe and secure environment in which to live.

The single most important thing I feel like I’ve learned is that we already have all the values we need to care about climate change in our hearts, no matter who we are and what part of the spectrum we come from. We just have to figure out how to connect those values to the issue of climate. (Applause.)

MR. DICAPRIO: Katharine, well put. Yes. Does our planet — and this is one of the questions I posed to many scientists while doing the film — does our planet have the ability to regenerate if we do the right things? Or has there been enough lasting damage that can never be undone? Have we put enough carbon into the atmosphere that we’re going to feel the repercussions of climate change for decades to come? And a second question to that — do you see any cutting-edge technology besides solar and wind, any bright spots on the horizon that suggest we can rapidly change this course? For example, fusion.

MS. HAYHOE: Yes. So just like smoking, we know that if you’ve already smoked for a certain amount of time there’s some damage that has been done. When is the best time to stop smoking? Today? If not today, tomorrow? If not then, the next day? But we know that the longer we’ve been doing it the greater the repercussions.

So, in the case of climate change, if we could flip a magic switch and turn off all our carbon emissions today, we would still see the impact of the Industrial Revolution on our planet for well over 5,000 years. That’s how long we would see it.

But, on the other hand, there’s still plenty of time to avoid the worst of the impacts. If we act now. Every year that goes by without serious action is one more year of smoking, essentially, that increases our risk of lung cancer, so to speak. Except we’re not talking about our own lungs, we’re talking about the planet.

So there is an urgency to it. But there’s also hope, because by acting we can change the future. The future really is in our hands, because for the first time in the history of the human race on this planet, we are the ones in the driver’s seat of climate. It is both frightening as well as an opportunity that we cannot afford to lose.

So, technologies. You’ve already gone through great ones. There are so many amazing ones. Like in West Texas were some smart guys who had an idea. They saw oil wells. What if we used wind energy to pump water down those oil wells under high pressure so that when it wasn’t windy we could let that water back up to turn the turbines and make electricity. That’s a pretty cool idea.

I would love to live in a house where the shingles are solar panels, where the walls are painted with solar paint, where I had one — power walls in the garage storing the energy overnight, and I plug in my electric car when I get home. We would all like to live in a world where our bike paths and even our highways are made out of solar panels, where everything that we do is constantly being renewed, and we know that we have a source of energy that is never going to run out on us and that does not pollute our air.

I was amazed — and this is a scientist speaking here — I was amazed to learn that here in the United States, on average, every year, 200,000 people die from air pollution from burning fossil fuels. It’s over 5 million around the world — 200,000 people. Imagine if those 200,000 people were dying from a different cause. Imagine some of the causes we’re told about today whenever you turn on the news — things that we should be afraid of. Air pollution, simple air pollution alone gives us all the reason in the world we need to shift towards clean energy. Add on climate change, add on the fact that, as the President mentioned a while ago, developing countries need energy. There’s a billion people living in energy poverty today, with no access to energy.

But if you add up all the fossil fuel resources in Southeast Asia and Africa, they have less than 10 percent of the world’s fossil fuels. So the answer for the billion people living in energy poverty is not to do it the same way we did 300 years ago. I mean, that’s honestly a very colonialistic attitude to say, no, you have to go back to the 1700s and do it that way. It’s like saying you have to go through the party telephone, and then you can get your own telephone, and then you can get a cellphone in another 150 years. That’s not the way the world works.

We are leapfrogging over the old technology, and the answer is we can do it because it’s taking us to a better and a more secure place. (Applause.)

MR. DICAPRIO: I got the opportunity to sit with the head of NASA, and you’ll see a lot of this in the film, but he basically projected the next 20 to 30 years. And he started talking about specifically the United States and the possibility of another Dust Bowl coming up. I asked about my home state of California and the wildfires and the droughts that are occurring there. And he said you can expect to continue that.

Do you agree that — we’re going to feel some of the repercussions of climate change in the form of rising sea levels, more intense hurricanes, and we’re going to see droughts and wildfires like that start to occur in the future. What do you think the future is going to look like for us if we do not take immediate action? Do you think we’ll be able to sustain the projected levels of what’s going to happen to our planet for the next 20 years? Or do you think that if we don’t take immediate action things are going to get exponentially worse?

MS. HAYHOE: So nine times out of ten, the way climate change affects us is not through some strange thing that we’ve never seen before. It’s not like a biblical plague of locusts arriving. It’s through taking what you just referred to — it’s taking the ways that we’re already vulnerable to climate and weather today.

How is D.C. vulnerable? Heatwaves, flooding, snowstorms. How is Texas vulnerable? Droughts, dust bowls, flooding. When we look at all the ways we’re already vulnerable, and nine times out of ten, that is exactly how climate change is going to impact us — by changing the risks of these events. And that’s what you already talked about. It isn’t a single event where we can point out, we can say, okay, that event was definitely climate change, but that event was 100 percent natural.

It’s more like climate change is taking the natural weather dice — and there’s always a chance of rolling a double six, an event that has a huge impact on us, economically. And climate change is sneaking in when we’re not looking and it’s taking another one of those numbers and replacing it with a six, and then another number and replacing it with a six. So the chances of rolling that double six are increasing the further we go down this road.

THE PRESIDENT: One thing I’d say, Leo, and I think Katharine alluded to this — another analogy to think about is we’re heading towards a cliff at 90 miles an hour. And if we hit the brakes, we don’t come to an immediate stop without spinning out of control. And so what we have to do is we have to tap the brakes. And if we tap the brakes now, then we don’t go over the cliff.

So when you think about climate change, there’s a big difference between the oceans rising three feet or the oceans rising 10 feet. Three feet is going to be expensive and inconvenient and disruptive. And we already see that — if you live in Miami right now — and I think, in fact, in your film you reference this — there are sunny days where, at noon, suddenly there’s two feet of water in the middle of the streets. And the reason is because as the oceans and the tides rise, Miami is on pretty porous rock, so it’s not even sufficient to build like a wall because it’s coming up through the ground.

And it’s going to be really expensive for Miami with three feet of water — or three feet of higher ocean. But it’s probably manageable. Once you start getting to 10 feet, then you don’t have South Florida. There will still be Florida, but it will be the Florida that will look like maybe a million years ago. And that’s a lot of property value. South Beach and Coral Gables and there are a lot of really nice spots. (Laughter.)

My hometown of Hawaii, Honolulu — Honolulu will still be there, but three feet just means you’re moving houses a little bit back from the beach. Ten feet means the beach doesn’t exist. And so the ramifications of whether we work on this now, steadily and make progress, or we don’t could mean the difference between huge disruptions versus adaptations that are expensive and inconvenient, but that don’t fundamentally change the shape of our society or put us into potential conflict.

I’m using examples here in the United States. Poor countries are obviously much more vulnerable. If you see a change in monsoon patterns in the Indian subcontinent where you’ve got potentially a billion people who are dependent on a certain pattern of rains, the Himalayas getting a certain amount of snowpack, et cetera, and those folks’ margin of error is so thin that you might end up seeing migrations of hundreds of millions of people, which invariably will create significant conflict.

There’s already some really interesting work — not definitive, but powerful — showing that the droughts that happened in Syria contributed to the unrest and the Syrian civil war. Well, if you start magnifying that across a lot of states, a lot of nation states that already contain a lot of poor people who are just right at the margins of survival, this becomes a national security issue.

And that’s why, even as we have members of Congress who scoff at climate change at the same time as they are saluting and wearing flag pins and extolling their patriotism, they’re not paying attention to our Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Pentagon who are saying that this is one of the most significant national security threats that we face over the next 50 years.

ll of which is to say that as hard as it is for us to start acting now to solve a problem that has not fully manifested itself yet, this is going to be a really important test for humanity and our political system. And it’s a test that requires everybody to do better. It requires me to do better, as somebody who’s got a voice. It requires Katharine and scientist to communicate more effectively. Everybody should take a lesson from Katharine on how to explain this stuff in ways that people understand. (Applause.)

it requires us reaching out to the faith community in ways that Katharine has done a really good job of, because there are a lot of evangelicals who are actually generally on the conservative side of the spectrum that care deeply about this planet that God made. It requires us to reach out to sportsmen and hunters and fishermen who may not agree at all on Second Amendment issues, but they sure like and understand the notion that they’ve got a forest where they can go out and — although they probably don’t want to be mauled by a grizzly bear — (laughter) — that looks a little severe. (Laughter.)

So all of us I think are going to have to do better than we’re doing in elevating this issue. And as I said before, better is good. We can start with existing technologies. I’ll just use one last example on this.

If we just had the energy efficiency of Japan, which is an island nation that doesn’t have a lot of fossil fuels, and so, historically, in their development path have been much more conscious about energy efficiency, we could reduce our energy consumption by 20 percent without changing our standard of living. Simple stuff like when you leave a room the light automatically goes off instead of it still be on.

A lot of companies are doing some smart work because it affects their bottom line. Our ability to measure in houses sort of smartly how much energy we’re using and minimizing waste of energy and heat can make a huge difference. Folks in Texas — air conditioning is a great invention, but nothing gets me more frustrated than seeing somebody and it’s 100 degrees outside and they’re wearing a sweater indoors because the air conditioning is turned up too high. But we do that everywhere — partly because of building design. You can’t open the windows, and so, as a consequence, you can’t use natural temperature regulators.

There’s a bunch of stuff that seems kind of simple and stupid, but would make a big dent. All those things have to start getting factored in. But we’ve got to change our politics. And as Leo said, it’s got to come from the bottom up. Until on a bipartisan basis, politicians feel that their failure to address this will cost them their seats, potentially, or will threaten their careers, then they’re going to continue to operate in ways that I think are really unproductive. (Applause.)

MS. HAYHOE: I began to study climate science over 20 years ago, and I have lived through the period where climate change has become one of the most politicized issues in the entire United States to where the number-one predictor of what our opinions are about climate change is nothing more than where we fall on the political spectrum.

The reality is, as my husband says, who is an evangelical pastor, a thermometer is not Democrat or Republican. It does not give us different numbers depending on how we vote. The science is what it is. If we say gravity isn’t real, and we step off a cliff, we’re going down anyway. But the solutions are political. Do we go with a cap and trade? Do we go with a carbon tax? Do we go with technological incentivizes? What do we do about other countries? How do we build states and businesses and communities? These are political and they should be debated up and down the halls. But what should not be debated is the fact that we are all human, we share this amazing home that we live in, and it is in all of our best interests to make sure that we leave it a better place for our children. (Applause.)

MR. DICAPRIO: This is my last question. President Obama, you use the Antiquities Act to preserve more acres of land and sea than any President since Teddy Roosevelt. (Applause.) I was going to say, let’s give him a round of applause, but they did that automatically. (Applause.) The great Teddy Roosevelt. How important is it to have a President who not only believes in the science of climate change, but one who understands that we must conserve these natural resources to create conditions that are conducive to a sustainable life for future generations?

THE PRESIDENT: Well, this goes to the point Katharine made about values. And I mentioned I grew up in Hawaii. Those of you who have been there, it’s a really pretty place. And the native Hawaiian traditions are so woven with nature and the sea and outdoors, and so that seeps into you when you grow up there.

But I tell you, I don’t know any place in the country where there isn’t someplace that evokes the same kind of sense of place and beauty. It may be a desert landscape. It may be a forest somewhere. It may be a mountain. And as my girls start getting older, I start thinking about grandkids — not soon. (Laughter.) But it’s natural you start thinking about sort of the next stages of your life and the idea that my grandkids wouldn’t see something I had seen, that — you can be a conservative Republican in Alabama, but you’ve got a memory of your dad taking you out hunting, and you being quiet and still, and you want to do that same thing with your kid. And it may be different than me taking my grandkid bodysurfing at Sandy Beach, but there’s the same feeling of wanting to pass that on. Of feeling deeply about it and caring deeply about it.

And I think one of the ways for us to tackle the climate change issue is also to lift up the power and the values that are embodied in conservation. It’s kind of a twofer. When we went out to Midway Islands, which is already a historic site because in part this was the turning point of World War II. There are people who revere this site because of its history in World War II, and the incredible courage and bravery of people who were outnumbered but ultimately were able to turn back a Japanese fleet that was on its way to Hawaii.

But we were up there, and this is water that’s just untouched. And you’re seeing monk seals diving in and swimming next to you, and turtles that are climbing up on the beach just to sun themselves, and it used to be there were 60,000 birds and now there are 3 million birds on this island — bunch of species that were about to go extinct. It all came back just in the span of one generation because of conservation. Well, not only is that creating incredible beauty, but it also means now that you have this huge preserve of ocean that is not contributing to climate change.

And so I think these two things go hand in hand. In the same way that the issue of air pollution and disease is, in some ways, a way to get at the climate change issue if people aren’t directly concerned about climate change. In China, frankly, part of the reason that people are — that the government there was willing to work with us, they’re number-one priority is political stability. And what they started noticing was the number one Twitter feed in China was the air quality monitor that was put out each morning by the U.S. embassy. It was the single thing that more Chinese looked at than anything because people couldn’t breathe in Beijing.

And smog is not the same as carbon dioxide, but it is generated by the same energy pattern usages. So if that’s where people are at right now and they want to be sure their kids are healthy, then let’s go after that. If they’re interested in conservation as a way to start thinking about climate change, let’s go after that. There are so many entry points into this issue and we’ve got to use all of them in order to convince people that this is something worth caring about.

But at the end of the day, the one thing I’m absolutely convinced about is, everybody cares about their kids, their grandkids, and the kind of world we pass on to them. And if we can speak to them about our responsibilities to the next generation, and we can give people realistic ways to deal with this so that they don’t feel like they’ve got to sacrifice this generation to do it, they have to put hardship on their kids now in order to save their grandkids — then I tend to be a cautious optimist about our ability to make change. But events like this obviously make a big difference and really help. (Applause.)

MR. DICAPRIO: Mr. President, Katharine, thank you so much for your time. I’m truly honored to premier this film here on the White House lawn. Like I said, this was a three-year endeavor. I learned so much and I’m going to let the film speak for itself as far as everything that I experienced on this journey.

Thank you so much for your time. Let’s give them a round of applause. Thank you.

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you, everybody. Appreciate you. Thank you. (Applause.)

MR. DICAPRIO: Thank you all for showing up.

THE PRESIDENT: Have fun, everybody.

MR. DICAPRIO: Enjoy the film.

President Obama Unprepared for Question on Dakota Access Pipeline's Violation of Indigenous Rights

While in Laos, President Barack Obama was caught unprepared by a question on Native Americans’ efforts to stop the construction of an oil pipeline in North Dakota. The pipeline, now under construction, is intended to transport fracked North Dakota oil to Iowa so that it can reach Texas refineries for export. The pipeline route crosses the Missouri River upstream of the Standing Rock Sioux water supply, through ancestral lands bordering the reservation.

The final question of a multinational youth town-hall forum came from a Malaysian activist “in solidarity with the indigenous people” of America “fighting to protect their ancestral land against the Dakota Access pipeline.”

Obama responded that one of his priorities is “restoring an honest and generous and respectful relationship with Native American tribes,” and argued that “we have actually restored more rights among Native Americans to their ancestral lands, sacred sites, waters, hunting grounds” during his term than under the Reagan, Clinton and Bush presidencies.

However, he said he’d “have to go back to my staff and find out how are we doing” on this particular violation of Native Americans’ ancestral lands, sacred sites, waters, and hunting grounds.

Transcript:

OBAMA: Malaysia. Okay, go ahead, right here.Q I’m from the state of Sabah in Malaysia. My question is, in solidarity with the indigenous people in—not my country, but in America itself. I just heard recently that this group of people is fighting to protect their ancestral land against the Dakota Access pipeline. So my question is, in your capacity, what can you do to ensure the protection of the ancestral land, the supply of clean water, and also environmental justice is upheld? (Applause.)

OBAMA: Well, it’s a great question. As many of you know, the way that Native Americans were treated was tragic. One of the priorities that I’ve had as President is restoring an honest and generous and respectful relationship with Native American tribes. And so we have made an unprecedented investment in meeting regularly with the tribes, helping them design ideas and plans for economic development, for education, for health that is culturally appropriate for them.

And this issue of ancestral lands and helping them preserve their way of life is something that we have worked very hard on. Now, some of these issues are caught up with laws and treaties, and so I can’t give you details on this particular case. I’d have to go back to my staff and find out how are we doing on this one.

But what I can tell you is, is that we have actually restored more rights among Native Americans to their ancestral lands, sacred sites, waters, hunting grounds. We have done a lot more work on that over the last eight years than we had in the previous 20, 30 years. And this is something that I hope will continue as we go forward. But it’s an excellent question.

At Lake Tahoe, President Obama Bashes Climate Deniers, Denies Surge in Carbon Pollution

You know, we tend to think of climate change as if it’s something that is just happening out there that we don’t have control over. But the fact is that it is man-made.It is not, “We think it is man-made.”

It is not, “We guess it is man-made.”

Not, “A lot of people are saying it’s man-made.”

It’s not, “I’m not a scientist, so I don’t know.”

You don’t have to be scientist. You have to read or listen to scientists to know that the overwhelming body of scientific evidence shows us that climate change is caused by human activity.

Obama noted that global warming is continuing at a frightening clip, with 2016 on pace to be the hottest year on record.

He later repeated one of his administration’s favored canards:During the first half of this year, carbon pollution hit its lowest level in a quarter of a century.

Obama is referring to the decline in carbon-dioxide emissions from electricity production in the U.S., using “carbon” as a synonym for “carbon dioxide.” However, the decline in CO2 emissions has been matched by a surge in methane emissions, another carbon-based greenhouse gas.

Furthermore, the U.S. has been dramatically increasing its production of oil and natural gas, helping fuel the continued global surge in carbon pollution during Obama’s presidency.

Full video of Obama’s speech:

Full transcript:

Hello, Lake Tahoe! [applause]This is really nice. I, I will be coming here more often. [cheers and applause]

You know, my transportation won’t be as nice but I’ll be able to spend a little more time here. First of all, I want to thank Harry Reid. [applause]

And, because he is a captive audience he doesn’t actually like people talking about him but he is stuck here so I’m going to talk about him for a second. You know, Harry grew up in a town that didn’t have much. No high school, no doctors office. Searchlight sure didn’t have much grass to mow or many trees to climb. It didn’t look like this. So when Harry discovered a lush desert oasis down the road called Paiute Springs, he fell in love. And when Harry met the love of his life, he couldn’t wait to take her there but when he got to the green spring that Harry remembered, he was devastated to see that the place had been trashed. And that day Harry became an environmentalist. And he has been working hard ever since to preserve the natural gifts of Nevada, and these United States of America. [cheering] Harry has protected fish and wildlife across the state. He helped to end a century-old water war. He created Nevada’s first and only national park. Right after I took office the very first act Harry’s Senate passed was one of the most important conservation efforts in a generation. We protected more than two million acres of wilderness and thousands of miles of trails and rivers. That was because of Harry Reid. [cheering] [applause]

Last summer thanks to Harry Reid’s leadership we protected more than 700,000 acres of mountains and valleys right here in Nevada, establishing the basin and Range National Monument. Two decades ago the senator from Searchlight trained a national spotlight right here on Lake Tahoe. And as he prepares to ride off into the sunset, although I don’t want him getting on a horse, this 20th anniversary summit proves that the light Harry lit shines as bright as ever. [cheers and applause]

In a few months I will be riding off into that same sunset. No, it’s true. It’s okay. I’m still, I’m going to be coming around, I told you. I just won’t have marine one. I will be driving. But, but let me tell you one of the great pleasures of being president is having strong relationships with people who do the right thing. They get criticized, they have got a tough job but they get in this tough business because ultimately they care about this country and they care about the people they represent. And that is true of Dianne Feinstein. [cheers and applause]

That is true of Barbara Boxer. That is true of the outstanding governor of California, Jerry Brown. [cheers and applause]

That’s true of our outstanding folks who work for the department of interior and work for the, and, who help look after our forests, that help after our national parks, but help manage our water and try to conserve the wildlife and the birds and all of the things that we want to pass on to the next generation. And, so I’m going to miss the day-to-day interactions that I’ve gotten, and I will miss Harry though he is not a sentimental guy. We talked backstage, anybody who has gotten on phone with Harry Reid, you will be mid conversation, once he is finished with the whole point of the conversation, you will still be talking and you realize he has hung up. He does that to the President of the United States. [laughter] And it takes you like three or four of these conversations to realize he is not mad at you, but he doesn’t have much patience for small talk. But Harry is tough. I believe he is going to go down as one of the best leaders that the senate ever had. I could not have accomplished what I accomplished without him being at my side. So, I want to say publicly, to the people of Nevada, to the people of Lake Tahoe, to the people of America, I could not be prouder to have worked alongside the democratic leader of the senate, Harry Reid. Give him a big round of applause. [cheers and applause]

So it’s special to stand on the shores of Lake Tahoe. I have never been here. No, I, it is not like I didn’t want to come. Nobody invited me. I didn’t know if I had a place to stay. So now that I have, I finally got here I’m going to come back. [cheering] and, and I want to come back not just because it’s beautiful, not just because—not just because I love you back. Not just because the Godfather II is maybe my favorite movie. I was flying over the lake I was thinking about Fredo. [laughter] Tough. But, this place is spectacular because it is one of the highest, deepest, oldest and purest lakes in the world. [cheering] [applause]

It’s been written the lake’s waters were once so clear when you were out on a boat you felt like you were floating in a balloon, unless you were Fredo. It has been written that the air here is so is fine it must be the same air that the angels breathe. So, it’s no wonder that for thousands of years this place has been a spirit—spiritual one. For the Washoe people it is center of their world. [applause]

Just as this place is sacred to Native Americans it should be sacred to all Americans and that’s why we’re here, to protect this special pristine place, to keep these waters crystal clear. To keep air as pure as heavens. To keep alive the spirit and keep this truth, challenges of climate change are linked.

[inaudible] Okay, I’m sorry. I got you. Okay. I got you. Thank you. That’s a great banner. I’m about to talk about it though, so you’re interrupting me. Now, I was going to talk about climate change and why it is so important. You know, we tend to think of climate change as if it’s something that is just happening out there that we don’t have control over. But the fact is that it is man-made. It is not, “We think it is man-made.” It is not, “We guess it is man-made.” Not, “A lot of people are saying it’s man-made.” It’s not, “I’m not a scientist, so I don’t know.”

You don’t have to be scientist. You have to read or listen to scientists to know that—[cheering] that the overwhelming body of scientific evidence shows us that climate change is caused by human activity. And when we protect our lands, it helps us protect the climate for the future. So conservation is critical, not just for one particular spot, one particular park, one particular lake. It is critical for our entire ecosystem and conservation is more than just putting up a plaque and calling something a park. [applause]

We embrace conservation because healthy, diverse lands and waters help us build resilience to climate change. We do it to free more of our communities and plants and animals and species from wildfires, and droughts and displacement. We do it because when most of the 4.5 million people who come to Lake Tahoe every year are tourists, economies like this one live or die by the health of our natural resources. [applause]

We do it because places like this nurture and restore the soul and we want to make sure that’s there for our kids too. [applause]

Now as a former Washo tribe leader once said, the health of the land and the health of the people are tied together and what happens to the land also happens to the people. That is why we worked so hard, everybody on the stage, Harry’s leadership, the work we’ve done in our administration to preserve treasures like this for future generations. And we have proven that the choice between our environment, our economy and our health is a false one. We’ve got to strengthen all of them together. [applause]

In the 20 years that President Clinton and Senator Reid started this summit, they improved habitats, improved roads, stopped pollution and stopped wildfires. That is especially important that the severe drought, all of you know and can see with your own eyes. A single wildfire in a dangerously flammable Lake Tahoe basin can erase decades of progress when it comes to water quality. It endangers one of the epicenters of food production in California. Changing climate threatens even the best conservation efforts.

Keep in mind, 2014 was the warmest year on record, until you guessed it, 2015. And now 2016 is on pace to be even hotter. For 14 months in a row now the earth has broken global temperature records. Lake Tahoe’s average temperature is rising at fastest rate ever and its temperature is the warmest on record. Because climate and conservation are challenges that go hand in hand, our conservation mission is more urgent than ever. Everybody who is here, including those who are very eager for me to finish so they can listen to the Killers. [cheering] [laughter]. I’ve only got a few more pages. Our conservation effort is more critical, more urgent than ever. And we made this a priority from day one. We, as Harry mentioned, protected more acres of public lands and water than any administration in history. Now—[cheers and applause]

Last week alone we protected land, water and wildlife from Maine to Hawaii. Including creation of the world’s largest marine protected area. [cheers and applause]

And, apropos of that young lady’s sign, we have been working on climate change on every front. We worked to generate more clean energy, use less dirty energy, waste less energy overall. In my first month in office Harry helped America make the single largest investment in renewable energy in our history. Dianne Feinstein, Barbara Boxer, have been at the forefront of this. Jerry Brown has been doing incredible legislative work in his state. These investments that helped drive down the cost of clean power, so it is finally cheaper than dirty power in a lot of places. It helps us multiply wind power threefold, solar power more than 30 fold. It has created tens of thousands of good jobs. It is adding to paychecks, subtracting from energy bills. It has been the smart and right thing to do. [cheers and applause]

Then one year ago this month we finalized the Clean Power Plan that spurs new sources of energy and gives states the tools to limit pollutions that power plants spew into the sky. As I mentioned last week, California passed an ambition plan to cut carbon pollution and Jerry, I know you agree, more states need to follow California’s lead. [applause]

On a national level we’ve enacted tough fuel economy standards for cars which means you can drive further on a gallon of gas. It will save you your pocketbook, and save the environment. We followed that up with the first-ever standards for commercial trucks, vans and buses. And as a consequence, during the first half of this year, carbon [dioxide] pollution hit its lowest level in a quarter of a century, and by the way, during the same time, we have had the longest streak of job creation on record. The auto industry is booming. There is no contradiction between being smart on the environment and having a strong economy and we got to keep it going. [cheers and applause]

So, so this isn’t just a challenge, this is an opportunity. And today in Tahoe we’re taking three more significant steps to boost conservation and climate action. First, we’re supporting conservation projects across Nevada to restore watersheds, stop invasive species, and further reduce the risks posed by hazardous fuels and wildfires. Number two. We’re incentivizing private capital to come off the sidelines and contribute to conservation because government can’t do it alone. Number three, in partnership with California we’re going to reverse the deterioration of the Salton Sea before it is too late. That will help a lot of folks all across the west. [applause]

So, so we’re busy. And from here I’m going to travel to my original home state of Hawaii where the United States is proud to host the World Conservation Congress for the first time. Tomorrow I’m going to go to Midway to visit the vast marine area we just created. And to honor those who sacrificed their lives to protect our freedom. [cheers and applause]

Then I head to China with whom we have partnered as the world’s two largest economies and two largest carbon emitters to set historic climate targets that will lead the rest of the world to cleaner, more secure future. [applause]

So just two back to quote from Marshall Elder. What happens to the land also happens to the people. I made it a priority in my presidency to protect the natural resource we inherited because we shouldn’t be the last to enjoy them. Just as the health of the land and people are tied together, just as climate and conservation are tied together, we share a sacred connection with those who are going to follow us. I think about my two daughters. I think about Harry’s 19 grandchildren. Yeah, that is a lot of grand kids. [laughter]. The future generations who deserve clean water and clean air that will sustain their bodies and sustain their souls. Jewels like Lake Tahoe. And it is not going happen without a lot of hard work and if we pretend a snowball in winter means nothing’s wrong. It will not happen how we boast we’ll scrap international treaties or, or have elected officials who are alone in the world in denying climate change. Or put our energy and environmental policies in the hands of big polluters. It is not going to happen if we pay lip service to conservation but then refuse to do what’s needed.